By Amy Howe

on Jun 23, 2021 at 12:13 pm

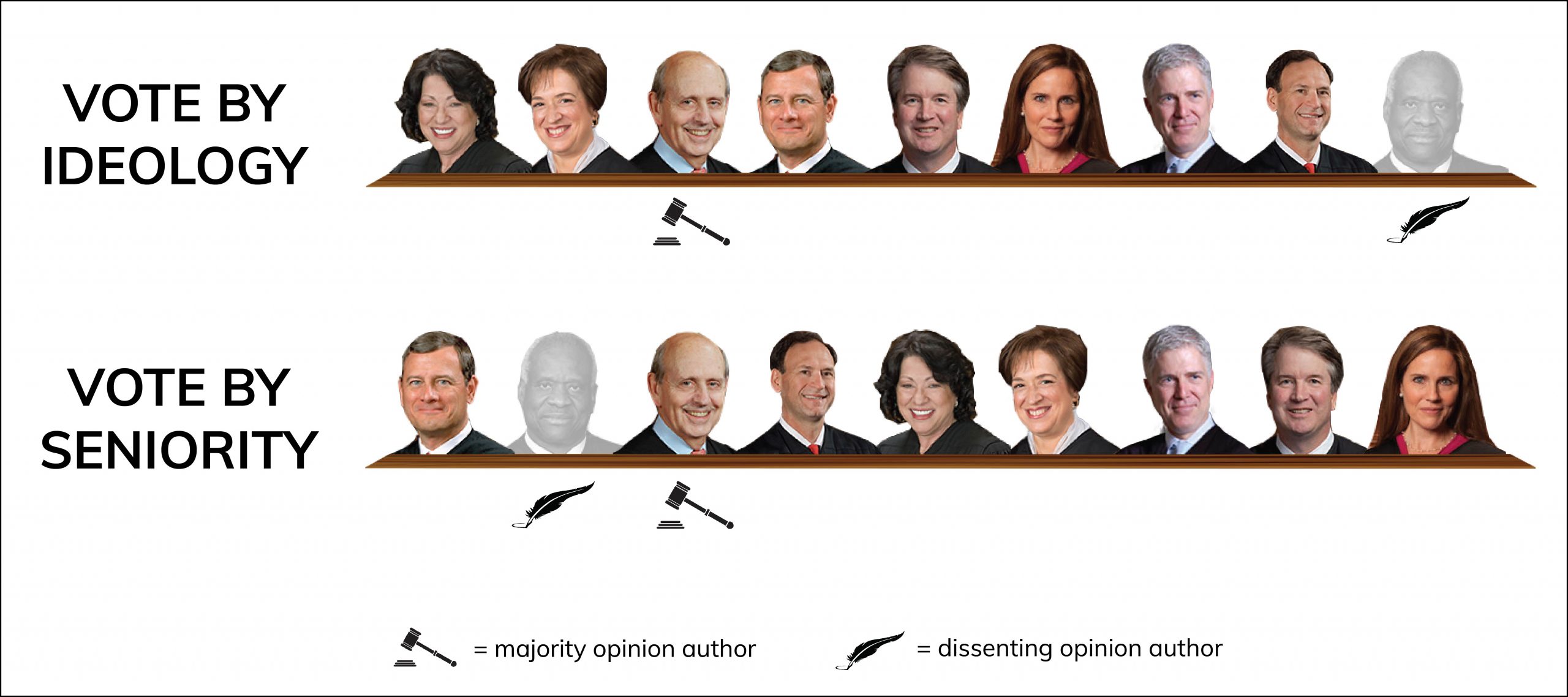

A Pennsylvania school district on Wednesday may have won the war over regulating off-campus student speech, but it lost the battle over a cheerleader’s profanity-laden complaint on Snapchat. The justices ruled that the First Amendment allows schools to regulate at least some student speech that occurs off campus. But, by a vote of 8-1, the justices agreed with the cheerleader that her one-year suspension from the cheerleading team nonetheless violated the First Amendment.

The case, Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., began in 2017, when 14-year-old Brandi Levy did not make her public school’s varsity cheerleading team. Levy expressed her disappointment on the social-media app Snapchat by posting a photo in which she had her middle finger raised, with the caption “Fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything.” Although Levy’s snap was only visible for 24 hours to 250 of her friends, coaches saw screenshots of the post and she was suspended from the junior varsity team for a year on the ground that the post violated team and school rules. Levy went to court, where she argued that the suspension violated the First Amendment. When the lower courts agreed, the school district went to the Supreme Court, which in January agreed to weigh in.

The court’s opinion was by Justice Stephen Breyer, who wrote that – unlike the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit – the majority did not believe that “the special characteristics that give schools additional license to regulate speech always disappear when a school regulates speech that takes place off campus.” The school may have a substantial interest in regulating, Breyer suggested, a variety of different kinds of off-campus conduct – for example, severe bullying, threats aimed at teachers or students, participation in online school activities or hacking into school computers.

On the other hand, Breyer observed, there are three features of off-campus speech that will make it less likely that schools will have an interest in regulating it. First, a student’s off-campus speech will generally be the responsibility of that student’s parents. Second, any regulation of off-campus speech would cover virtually everything that a student says or does outside of school. And third, the school has an interest in protecting unpopular speech and ideas by its students. Breyer explained that the court left “for future cases to decide where, when, and how these features mean the speaker’s off-campus location will make the critical difference” in determining whether speech can be regulated.

But even if schools can in some circumstances regulate students’ off-campus speech, Breyer continued, the decision to suspend Levy for her snap still violated the First Amendment. If she had been an adult, Levy’s speech would normally be protected by the First Amendment, Breyer reasoned. Moreover, she created the snap off school grounds on a weekend, and there is no evidence that it caused the kind of substantial disruption that would justify her suspension. Breyer acknowledged that some people might regard the substance of Levy’s snap as so trivial that it is not the kind of speech worthy of the First Amendment’s protection. “But sometimes it is necessary to protect the superfluous in order to preserve the necessary,” Breyer concluded.

Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter. He cited “150 years of history supporting the coach” and argued that the majority opinion “reaches the wrong result.” Schools, he contended, “historically could discipline students in circumstances like those presented here.”